Trips and Activities for Syncro Safari, Death Valley '17

Titus Canyon - Tuesday, April 18

4WD Route - Death Valley’s Drive-Thru Slot Canyon

Titus Canyon is widely regarded as one of the best destinations for a driving tour in Death Valley as it passes through 27 miles of scenery featuring high mountain peaks, remnants of a ghost town, and high towering canyon narrows. Difficulties encountered on a one-way drive through Titus Canyon include having sufficient HC (high clearance) to pass through a few rough sections of road and driving along an exposed section with sheer cliffs on one side.

The trail, also known as Leadfield Road is a strip of dirt heads straight to the foothills of the Grapevine Mountains.The road is closed during the winter months when there is snow in the pass to the canyon. A well-maintained gravel road but steep and narrow in a few places. Four-wheel drive seldom necessary under dry conditions. Road is closed when rain is expected due to extreme flash-flood danger through narrowest part of Titus Canyon. May also close with winter snows.

The highest point of the road is Red Pass at an elevation of 5,213 ft above the sea level. As the road reaches the foothills, it starts to climb and meander among the sagebrush and red rock outcroppings. The road becomes steeper and narrower as it approaches Red Pass, aptly named for its red rocks and dirt. The surface on this gravel road is often loose, especially along the sides of the road. It makes necessary to drive carefully and slow down whenever approaching an oncoming car. Two-wheel-drive, high-clearance recommended; four-wheel-drive may be needed after adverse weather conditions. Two-way section from west OK for two-wheel-drive, standard clearance vehicles. Many sections are steep and rocky that a passenger vehicle would not be able to pass.

Titus Canyon is widely regarded as one of the best destinations for a driving tour in Death Valley as it passes through 27 miles of scenery featuring high mountain peaks, remnants of a ghost town, and high towering canyon narrows. Difficulties encountered on a one-way drive through Titus Canyon include having sufficient HC (high clearance) to pass through a few rough sections of road and driving along an exposed section with sheer cliffs on one side.

The trail, also known as Leadfield Road is a strip of dirt heads straight to the foothills of the Grapevine Mountains.The road is closed during the winter months when there is snow in the pass to the canyon. A well-maintained gravel road but steep and narrow in a few places. Four-wheel drive seldom necessary under dry conditions. Road is closed when rain is expected due to extreme flash-flood danger through narrowest part of Titus Canyon. May also close with winter snows.

The highest point of the road is Red Pass at an elevation of 5,213 ft above the sea level. As the road reaches the foothills, it starts to climb and meander among the sagebrush and red rock outcroppings. The road becomes steeper and narrower as it approaches Red Pass, aptly named for its red rocks and dirt. The surface on this gravel road is often loose, especially along the sides of the road. It makes necessary to drive carefully and slow down whenever approaching an oncoming car. Two-wheel-drive, high-clearance recommended; four-wheel-drive may be needed after adverse weather conditions. Two-way section from west OK for two-wheel-drive, standard clearance vehicles. Many sections are steep and rocky that a passenger vehicle would not be able to pass.

Rhyolite Ghost Town - Tuesday, April 18

Rhyolite’s birth was brought about by Shorty Harris and E. L. Cross, who were prospecting in the area in 1904. They found quartz all over a hill, and as Shorty describes it “... the quartz was just full of free gold... it was the original bullfrog rock... this banner is a crackerjack” declared Shorty! “The district is going to be the banner camp of Nevada. I say so once and I’ll say it again.” At that time there was only one other person in the whole area: Old Man Beatty who lived in a ranch with his family five miles away. Soon the rush was on and several camps were set up including Bullfrog, the Amargosa and a settlement between them called Jumpertown.

There were over 2000 claims covering everything in a 30 mile area from the Bullfrog district. The most promising was the Montgomery Shoshone mine, which prompted everyone to move to the Rhyolite townsite. The town immediately boomed with buildings springing up everywhere. One building was 3 stories tall and cost $90,000 to build. A stock exchange and Board of Trade were formed. The red light district drew women from as far away as San Francisco. There were hotels, stores, a school for 250 children, an ice plant, two electric plants, foundries and machine shops and even a miner’s union hospital.

The town citizens had an active social life including baseball games, dances, basket socials, whist parties, tennis, a symphony, Sunday school picnics, basketball games, Saturday night variety shows at the opera house and pool tournaments. In 1906 Countess Morajeski opened the Alaska Glacier Ice Cream Parlor to the delight of the local citizenry. That same year an enterprising miner, Tom T. Kelly, built a Bottle House out of 50,000 beer and liquor bottles.

In April 1907 electricity came to Rhyolite, and by August of that year a mill had been constructed to handle 300 tons of ore a day at the Montgomery Shoshone mine. It consisted of a crusher, 3 giant rollers, over a dozen cyanide tanks and a reduction furnace. The Montgomery Shoshone mine had become nationally known because Bob Montgomery once boasted he could take $10,000 a day in ore from the mine. It was later owned by Charles Schwab, who purchased it in 1906 for a reported 2 to 6 million dollars.

The financial panic of 1907 took its toll on Rhyolite and was seen as the beginning of the end for the town. In the next few years mines started closing and banks failed. Newspapers went out of business, and by 1910 the production at the mill had slowed to $246,661 and there were only 611 residents in the town. On March 14, 1911 the directors voted to close down the Montgomery Shoshone mine and mill. In 1916 the light and power were finally turned off in the town.

Today you can find several remnants of Rhyolite’s glory days. Some of the walls of the 3 story bank building are still standing, as is part of the old jail. The train depot (privately owned) is one of the few complete buildings left in the town, as is the Bottle House. The Bottle House was restored by Paramount pictures in Jan, 1925. The ghost town of Rhyolite is on a mixture of federal and private land. It is not within the boundary of Death Valley National Park.

There were over 2000 claims covering everything in a 30 mile area from the Bullfrog district. The most promising was the Montgomery Shoshone mine, which prompted everyone to move to the Rhyolite townsite. The town immediately boomed with buildings springing up everywhere. One building was 3 stories tall and cost $90,000 to build. A stock exchange and Board of Trade were formed. The red light district drew women from as far away as San Francisco. There were hotels, stores, a school for 250 children, an ice plant, two electric plants, foundries and machine shops and even a miner’s union hospital.

The town citizens had an active social life including baseball games, dances, basket socials, whist parties, tennis, a symphony, Sunday school picnics, basketball games, Saturday night variety shows at the opera house and pool tournaments. In 1906 Countess Morajeski opened the Alaska Glacier Ice Cream Parlor to the delight of the local citizenry. That same year an enterprising miner, Tom T. Kelly, built a Bottle House out of 50,000 beer and liquor bottles.

In April 1907 electricity came to Rhyolite, and by August of that year a mill had been constructed to handle 300 tons of ore a day at the Montgomery Shoshone mine. It consisted of a crusher, 3 giant rollers, over a dozen cyanide tanks and a reduction furnace. The Montgomery Shoshone mine had become nationally known because Bob Montgomery once boasted he could take $10,000 a day in ore from the mine. It was later owned by Charles Schwab, who purchased it in 1906 for a reported 2 to 6 million dollars.

The financial panic of 1907 took its toll on Rhyolite and was seen as the beginning of the end for the town. In the next few years mines started closing and banks failed. Newspapers went out of business, and by 1910 the production at the mill had slowed to $246,661 and there were only 611 residents in the town. On March 14, 1911 the directors voted to close down the Montgomery Shoshone mine and mill. In 1916 the light and power were finally turned off in the town.

Today you can find several remnants of Rhyolite’s glory days. Some of the walls of the 3 story bank building are still standing, as is part of the old jail. The train depot (privately owned) is one of the few complete buildings left in the town, as is the Bottle House. The Bottle House was restored by Paramount pictures in Jan, 1925. The ghost town of Rhyolite is on a mixture of federal and private land. It is not within the boundary of Death Valley National Park.

Artists Palette - Wednesday, April 19

This scenic loop drive shows you the diversity of color that nature has provided with the help of various minerals, oxidation, erosion and of course time. The colors range is purple, green, yellow, white, peach, orange, red, brown, gray, and black. Quite breathtaking, the best time to view this is close to dusk. While traveling the loop you will have a great view of the valley below, as well as the mountain range on the other side. This is a popular place for cyclist, so please keep an eye out for them while traveling. Artists Drive is a 9 mile one-way road with an entrance and exit from Badwater Road.

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel south on 190 about 1.6 miles and turn right onto Badwater Road. Drive south on Badwater Road about 8.6 miles (passing the Artists Drive EXIT at about 4.8 miles) and turn left into Artists Drive entrance. Enjoy!

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel south on 190 about 1.6 miles and turn right onto Badwater Road. Drive south on Badwater Road about 8.6 miles (passing the Artists Drive EXIT at about 4.8 miles) and turn left into Artists Drive entrance. Enjoy!

Devil's Golf Course - Wednesday, April 19

The gnarled terrain of an ancient evaporated lake contains crystals of almost pure table salt. The craggy lake bottom is complex and intricate with crystals in various stages of development. Deposited by ancient salt lakes and shaped by winds and rain, the crystals are forever changing. The Death Valley saltpan is one of the largest saltpans in North America. Salt continues to be deposited by recurring floods that occasionally submerge the lowest parts of the valley floor.

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel south on 190 about 1.6 miles and turn right onto Badwater Road. Drive south on Badwater Road about 11 miles and turn right and go about 1.7 miles on the dirt road which leads to the “Golf Course”.

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel south on 190 about 1.6 miles and turn right onto Badwater Road. Drive south on Badwater Road about 11 miles and turn right and go about 1.7 miles on the dirt road which leads to the “Golf Course”.

Badwater - Wednesday, April 19

The low, salty pool at Badwater, just beside the main park road is probably the best known and most visited place in Death Valley. The elevation here is 280 feet below sea level. The actual lowest point (-282 feet) is located a couple miles from the road and is not easily accessible - in fact its position varies. An enlarged parking area and other new facilities were constructed in fall 2003 to cope with the ever increasing visitor numbers at the site.

There is not much else to see apart from an orientation table, identifying many of the surrounding mountains. Look up! High in the rocky cliffs above the road, another sign reads 'SEA LEVEL', giving a good indication of just how low the land is. Far above this, the overlook at Dante's Peak has imposing views over Badwater and the surrounding desert.

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel south on 190 about 1.6 miles and turn right onto Badwater Road. Drive south on Badwater Road about 16.5 miles to the Badwater parking area.

There is not much else to see apart from an orientation table, identifying many of the surrounding mountains. Look up! High in the rocky cliffs above the road, another sign reads 'SEA LEVEL', giving a good indication of just how low the land is. Far above this, the overlook at Dante's Peak has imposing views over Badwater and the surrounding desert.

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel south on 190 about 1.6 miles and turn right onto Badwater Road. Drive south on Badwater Road about 16.5 miles to the Badwater parking area.

Mosaic Canyon Hike - Wednesday, April 19

Length: 4 miles out and back round trip

Time: 2.5 - 3 hours round trip for the full canyon

Difficulty: Moderate to Difficult

Elevation Gain: 1,200 ft

Location: The 2.3 mile graded Mosaic Canyon Road is located in Stovepipe Wells Village just across from Stovepipe Wells Campground.

Parking: A large gravel parking area. Buses and large RV's not recommended.

Closest Restroom: Stovepipe Wells Village at the general store and restaurant.

Route: Many hikers choose to hike to the first set of beautiful canyon narrows less than 0.5 miles into the canyon. One can choose to double back at any point depending on the length of hike you desire.

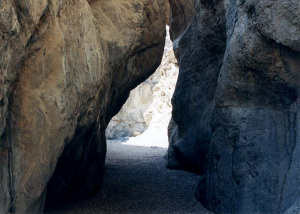

This short hike runs up a gravel wash into a narrow canyon with water-polished walls made of white marble and blue-gray conglomerate rocks in the Death Valley Wilderness Area. The water-polished conglomerate rocks look like mosaic tiles grouted onto the canyon wall, hence the name of the canyon. The bottom few feet of the canyon is a narrow slot that is only 2-3 feet wide in places, but the canyon generally feels open and airy. The best water-polished marble in the entire canyon is about 1/4 mile from the trailhead.

The trail starts in a wash and runs between 15-ft-tall alluvial cliffs, with the dark gray and brown cliffs of Tucki Mountain towering above them. You quickly get past the alluvial cliffs and into bedrock at the mouth of the canyon. At that point, you can see that the rocks at the edge of the wash are white. This is water-polished marble (metamorphosed limestone). The white is exposed on the edges of the wash because it is water polished; above the wash, a thick patina of desert varnish darkens the marble. The vegetation here is sparse as usual, and dominated by creosote bush with some pygmy cedar, Ephedra, and prickly Penstemon higher up.

At the narrows the canyon is mostly white, water-polished marble, but the west (right) side is layered: the base layer is marble, but that is overlain by a cobbly conglomerate, which in turn is overlain by more-recent, finer-grained conglomerate alluvial materials.

Scrambling up the winding narrows, the rock is water-sculpted and water-polished, and you can see many examples of the marble and conglomerate mosaic in the walls of the canyon. Later, the wash cut down through the rock, exposing the mosaic appearance. There are places along the edge of the wash where you can see that either the infilling process was not complete or the infill material has eroded away, revealing the 3-dimensional nature of the original rubble.

Time: 2.5 - 3 hours round trip for the full canyon

Difficulty: Moderate to Difficult

Elevation Gain: 1,200 ft

Location: The 2.3 mile graded Mosaic Canyon Road is located in Stovepipe Wells Village just across from Stovepipe Wells Campground.

Parking: A large gravel parking area. Buses and large RV's not recommended.

Closest Restroom: Stovepipe Wells Village at the general store and restaurant.

Route: Many hikers choose to hike to the first set of beautiful canyon narrows less than 0.5 miles into the canyon. One can choose to double back at any point depending on the length of hike you desire.

This short hike runs up a gravel wash into a narrow canyon with water-polished walls made of white marble and blue-gray conglomerate rocks in the Death Valley Wilderness Area. The water-polished conglomerate rocks look like mosaic tiles grouted onto the canyon wall, hence the name of the canyon. The bottom few feet of the canyon is a narrow slot that is only 2-3 feet wide in places, but the canyon generally feels open and airy. The best water-polished marble in the entire canyon is about 1/4 mile from the trailhead.

The trail starts in a wash and runs between 15-ft-tall alluvial cliffs, with the dark gray and brown cliffs of Tucki Mountain towering above them. You quickly get past the alluvial cliffs and into bedrock at the mouth of the canyon. At that point, you can see that the rocks at the edge of the wash are white. This is water-polished marble (metamorphosed limestone). The white is exposed on the edges of the wash because it is water polished; above the wash, a thick patina of desert varnish darkens the marble. The vegetation here is sparse as usual, and dominated by creosote bush with some pygmy cedar, Ephedra, and prickly Penstemon higher up.

At the narrows the canyon is mostly white, water-polished marble, but the west (right) side is layered: the base layer is marble, but that is overlain by a cobbly conglomerate, which in turn is overlain by more-recent, finer-grained conglomerate alluvial materials.

Scrambling up the winding narrows, the rock is water-sculpted and water-polished, and you can see many examples of the marble and conglomerate mosaic in the walls of the canyon. Later, the wash cut down through the rock, exposing the mosaic appearance. There are places along the edge of the wash where you can see that either the infilling process was not complete or the infill material has eroded away, revealing the 3-dimensional nature of the original rubble.

Darwin Falls Hike - Thursday, April 20

A waterfall in the middle of the arid desert. Named after Dr. Darwin French, Darwin Falls are truly unique and exceptional in every way. The year-round falls provide a water source for plants and wildlife.

Length: 2 miles out and back round trip

Time: 1.5 - 2 hours round trip

Difficulty: Moderate

Elevation Gain: 450 ft

Location: The unpaved Darwin Falls Road is located 1.2 miles west of Panamint Springs on CA-190. To the trailhead (first 2.5 mi), Darwin Falls Road from CA-190 is typically passable to a sedan, however it is much more comfortable in a high clearance vehicle.

Parking: Small gravel parking area. Not recommended for large RV's.

Closest Restrooms: No restrooms. The nearest facilities are located at the privately owned Panamint Springs Resort.

Route: Unmarked. From the bulletin board head past the gate and into the wash up the canyon. The unmarked route is fairly flat but rocky as it transitions from a desert wash into a high walled canyon. Inside the canyon thick vegetation, stream crossings, and large slick rocks require that hikers use caution as they work their way deeper into the oasis. Please protect this fragile resource. No swimming!

This short hike follows one of only four perennial streams in Death Valley National Park, leading through areas of riparian vegetation en route to a spectacular and rare desert waterfall. Darwin Falls is perhaps the most uncharacteristic locale in Death Valley National Park, its setting beyond the scope of most people’s perceptions of the quintessential desert landscape. Darwin Creek is one of the four perennial streams in the park’s more than three-million-acre expanse of desert valleys and mountains. Darwin Wash drains the westernmost reaches of the park, flowing from the volcanic tableland of Darwin Bench between the Inyo Mountains to the north and the Argus Range to the south.

Find the road to the Darwin Falls trailhead about 2 miles west of Panamint Springs on highway 190. From 190 turn left (south) and travel another 2.5 miles on the 2WD dirt road to the parking area marked for Darwin Falls. The hike is about ¾ mile each way and is undeveloped in places and can be “brushy”. Trail crosses small stream several times before reaching the falls.

A real “Oasis” in the desert.

Length: 2 miles out and back round trip

Time: 1.5 - 2 hours round trip

Difficulty: Moderate

Elevation Gain: 450 ft

Location: The unpaved Darwin Falls Road is located 1.2 miles west of Panamint Springs on CA-190. To the trailhead (first 2.5 mi), Darwin Falls Road from CA-190 is typically passable to a sedan, however it is much more comfortable in a high clearance vehicle.

Parking: Small gravel parking area. Not recommended for large RV's.

Closest Restrooms: No restrooms. The nearest facilities are located at the privately owned Panamint Springs Resort.

Route: Unmarked. From the bulletin board head past the gate and into the wash up the canyon. The unmarked route is fairly flat but rocky as it transitions from a desert wash into a high walled canyon. Inside the canyon thick vegetation, stream crossings, and large slick rocks require that hikers use caution as they work their way deeper into the oasis. Please protect this fragile resource. No swimming!

This short hike follows one of only four perennial streams in Death Valley National Park, leading through areas of riparian vegetation en route to a spectacular and rare desert waterfall. Darwin Falls is perhaps the most uncharacteristic locale in Death Valley National Park, its setting beyond the scope of most people’s perceptions of the quintessential desert landscape. Darwin Creek is one of the four perennial streams in the park’s more than three-million-acre expanse of desert valleys and mountains. Darwin Wash drains the westernmost reaches of the park, flowing from the volcanic tableland of Darwin Bench between the Inyo Mountains to the north and the Argus Range to the south.

Find the road to the Darwin Falls trailhead about 2 miles west of Panamint Springs on highway 190. From 190 turn left (south) and travel another 2.5 miles on the 2WD dirt road to the parking area marked for Darwin Falls. The hike is about ¾ mile each way and is undeveloped in places and can be “brushy”. Trail crosses small stream several times before reaching the falls.

A real “Oasis” in the desert.

Wildrose Charcoal Kilns - Thursday, April 20

In 1877 George Hearst’s Modock Consolidated Mining Company completed construction of the charcoal kilns in Wildrose Canyon. The charcoal produced by the kilns was to be used as fuel for two silver-lead smelters that Hearst had built in the Argus Range 25 miles to the west. The kilns operated until the summer of 1878 when the Argus mines, due to deteriorating ore quality, closed and the furnaces shut down. The Wildrose kilns employed about 40 woodcutters and associated workmen, and the town of Wildrose, a temporary camp located somewhere nearby, was home to about 100 people. Remi Nadeau’s Cerro Gordo Freighting Company hauled the charcoal to the smelters by pack train and wagon.

Each of the 10 kilns stands about 25 feet tall and has a circumference of approximately 30 feet. Each kiln held 42 cords of pinyon pine logs and would, after burning for a week, produce 2,000 bushels of charcoal. Considered to be the best surviving examples of such kilns to be found in the western states, the kilns owe their longevity to fine workmanship and to the fact that they were in use for such a short time.

The Wildrose Charcoal kilns are located in Wildrose Canyon on the western side of Death Valley National Park. Access the Wildrose Canyon road from California Highway 178 between Trona and Panamint Springs.

From Panamnit Springs take California Highway 190 east about 21 miles and take Emigrant Canyon Road south up and over Emigrant Pass about 21 miles and turn left up Wildrose Canyon. The Wildrose Charcoal Kilns are about 7 miles up this road. The last 3 miles of the road are unpaved and the road is subject to storm closures.

Each of the 10 kilns stands about 25 feet tall and has a circumference of approximately 30 feet. Each kiln held 42 cords of pinyon pine logs and would, after burning for a week, produce 2,000 bushels of charcoal. Considered to be the best surviving examples of such kilns to be found in the western states, the kilns owe their longevity to fine workmanship and to the fact that they were in use for such a short time.

The Wildrose Charcoal kilns are located in Wildrose Canyon on the western side of Death Valley National Park. Access the Wildrose Canyon road from California Highway 178 between Trona and Panamint Springs.

From Panamnit Springs take California Highway 190 east about 21 miles and take Emigrant Canyon Road south up and over Emigrant Pass about 21 miles and turn left up Wildrose Canyon. The Wildrose Charcoal Kilns are about 7 miles up this road. The last 3 miles of the road are unpaved and the road is subject to storm closures.

Lippincott Road and Racetrack Playa - Friday, April 21

Rough 4WD route to Death Valley's famous and

once mysterious moving rocks

Nestled in a remote valley between the Cottonwood and Last Chance Ranges, the Racetrack is a place of stunning beauty and mystery. The Racetrack is a playa--a dry lake-bed--best known for its strange moving rocks.

The Moving Rocks

The moving rocks, are two miles south of the Grandstand parking area. Walk at least a half mile toward the southeast corner of the playa for the best views of rocks and their tracks on the playa. Erosion cause rocks from the surrounding mountains to tumble to the surface of the Racetrack. Once on the floor of the playa the rocks move across the level surface leaving trails as records of their movements. Some of the moving rocks are large and have traveled as far as 1,500 feet. Throughout the years many theories have been suggested to explain the mystery of these rock movements. A research project has suggested that a rare combination of rain and wind conditions enable the rocks to move. A rain of about 1/2 inch, will wet the surface of the playa, providing a firm but extremely slippery surface. Strong winds of 50 mph or more, may skid the large boulders along the slick mud.

https://www.nps.gov/deva/planyourvisit/the-racetrack.htm

Our Route to the Racetrack... Lippincott Mine Road

(We'd plan to use this route through Saline Valley and Lippincott both there and back.)

Lippincott Mine Road is a 7-mile, low-range climb from the Saline Valley to the Racetrack Playa in Death Valley National Park. Calling it a low-range climb is an understatement. It's more accurate to say that Lippincott Mine Road is a serious, high-pucker-factor, mountain-goat trail.

On Saline Valley Road, there's a large rock cairn. Turn east, and just beyond is a sign that warms the heart of any dedicated 4-wheeler, "Caution...Route Ahead Not Recommended for Vehicle Travel." Even better: they're not kidding. It is a warning to take seriously. You're only 10 miles from the Racetrack, but 7 of those miles are going to be on a low-range mountain trail.

The trail rounds the foot of a mountain, then heads up a canyon that winds its way through spectacular scenery. The rocks are an interesting collage of volcanic lava, granite, sedimentary conglomerates and a lot of interesting quartz -- gold-bearing, perhaps, judging from the amount of mining and the number of prospect holes in the canyon.

The climb gets very serious; this is slow, low-range work. There are washouts, most of which have been repaired with rocks, and in places you'll only have a foot or so between your outside tire and a disaster. The drop gets hairy, too -- hundreds of feet, not straight down, but not enough of a slope to matter -- a mistake would be fatal.

There's an additional problem: if there's a breeze in the canyon, it will be coming from behind you, which, coupled with the low-range hard climb, can cause overheating. Watch your temperature gauge.

The road tops out at a saddle. This isn't the summit, but it's a good stopping point, and the view is fantastic. There's room to park with your grill in the wind to let things cool.

Further on, the pucker-factor eases as the cliff dropoffs are not as severe, but the trail remains a challenge with switchbacks and washouts and low-range climbs. The trail ends just beyond the summit at a nice bladed road, with another warning sign like the first for the traffic coming from the other direction.

From there it's a quick jaunt over to the south end of Racetrack Playa

once mysterious moving rocks

Nestled in a remote valley between the Cottonwood and Last Chance Ranges, the Racetrack is a place of stunning beauty and mystery. The Racetrack is a playa--a dry lake-bed--best known for its strange moving rocks.

The Moving Rocks

The moving rocks, are two miles south of the Grandstand parking area. Walk at least a half mile toward the southeast corner of the playa for the best views of rocks and their tracks on the playa. Erosion cause rocks from the surrounding mountains to tumble to the surface of the Racetrack. Once on the floor of the playa the rocks move across the level surface leaving trails as records of their movements. Some of the moving rocks are large and have traveled as far as 1,500 feet. Throughout the years many theories have been suggested to explain the mystery of these rock movements. A research project has suggested that a rare combination of rain and wind conditions enable the rocks to move. A rain of about 1/2 inch, will wet the surface of the playa, providing a firm but extremely slippery surface. Strong winds of 50 mph or more, may skid the large boulders along the slick mud.

https://www.nps.gov/deva/planyourvisit/the-racetrack.htm

Our Route to the Racetrack... Lippincott Mine Road

(We'd plan to use this route through Saline Valley and Lippincott both there and back.)

Lippincott Mine Road is a 7-mile, low-range climb from the Saline Valley to the Racetrack Playa in Death Valley National Park. Calling it a low-range climb is an understatement. It's more accurate to say that Lippincott Mine Road is a serious, high-pucker-factor, mountain-goat trail.

On Saline Valley Road, there's a large rock cairn. Turn east, and just beyond is a sign that warms the heart of any dedicated 4-wheeler, "Caution...Route Ahead Not Recommended for Vehicle Travel." Even better: they're not kidding. It is a warning to take seriously. You're only 10 miles from the Racetrack, but 7 of those miles are going to be on a low-range mountain trail.

The trail rounds the foot of a mountain, then heads up a canyon that winds its way through spectacular scenery. The rocks are an interesting collage of volcanic lava, granite, sedimentary conglomerates and a lot of interesting quartz -- gold-bearing, perhaps, judging from the amount of mining and the number of prospect holes in the canyon.

The climb gets very serious; this is slow, low-range work. There are washouts, most of which have been repaired with rocks, and in places you'll only have a foot or so between your outside tire and a disaster. The drop gets hairy, too -- hundreds of feet, not straight down, but not enough of a slope to matter -- a mistake would be fatal.

There's an additional problem: if there's a breeze in the canyon, it will be coming from behind you, which, coupled with the low-range hard climb, can cause overheating. Watch your temperature gauge.

The road tops out at a saddle. This isn't the summit, but it's a good stopping point, and the view is fantastic. There's room to park with your grill in the wind to let things cool.

Further on, the pucker-factor eases as the cliff dropoffs are not as severe, but the trail remains a challenge with switchbacks and washouts and low-range climbs. The trail ends just beyond the summit at a nice bladed road, with another warning sign like the first for the traffic coming from the other direction.

From there it's a quick jaunt over to the south end of Racetrack Playa

Other sites for future trips

(Not included in Death Valley '17)

(Not included in Death Valley '17)

Golden Canyon Hike

Golden Canyon is a short gorge that cuts into brightly colored sandstone rocks in many glowing shades of orange, gold and red, with the ever-present deep blue sky above making the hues seem especially sharp and intense. Once there was a paved road running up the whole length but this has long been disused and most sections have eroded away. Now, travel on foot is the only option, and the hike is one of the most popular in the national park. Trail guides describing numbered points of interest are available at the nearby parking lot.

The canyon is not particularly enclosed though some of its short tributaries are more narrow. The drainage gains elevation gradually, branches several times then ends quite abruptly after about 1 mile, at the base of high sandstone cliffs - a natural amphitheatre known as Red Cathedral, where the majority of visitors turn back though a longer trail forks south and continues through the multicolored badlands beneath Zabriskie Point, a trip of 4 miles in total. The junction is a few hundred yards south of the cathedral; the path starts by climbing quite steeply up an exposed slope of whitish earth to a high ridge beneath a protruding rock formation, a point which overlooks a wide area of fantastic badlands and canyons.

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel south on 190 about 1.6 miles and turn right onto Badwater Road. Drive south on Badwater Road about 2 miles and turn left and go up the short road to the Marble Canyon trailhead.

The canyon is not particularly enclosed though some of its short tributaries are more narrow. The drainage gains elevation gradually, branches several times then ends quite abruptly after about 1 mile, at the base of high sandstone cliffs - a natural amphitheatre known as Red Cathedral, where the majority of visitors turn back though a longer trail forks south and continues through the multicolored badlands beneath Zabriskie Point, a trip of 4 miles in total. The junction is a few hundred yards south of the cathedral; the path starts by climbing quite steeply up an exposed slope of whitish earth to a high ridge beneath a protruding rock formation, a point which overlooks a wide area of fantastic badlands and canyons.

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel south on 190 about 1.6 miles and turn right onto Badwater Road. Drive south on Badwater Road about 2 miles and turn left and go up the short road to the Marble Canyon trailhead.

Grotto Canyon Hike

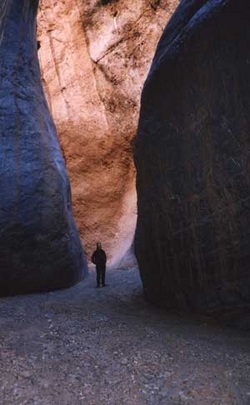

Many canyons slice into the steep, metamorphic rocks that form the slopes of Tucki Mountain, south of Stovepipe Wells in Death Valley National Park, and doubtless all are interesting although most are rather inaccessible and not easily followed. Exceptions are three close to the main highway CA 190 which have a recognized trail at least part of the way: Mosaic, Little Bridge and Grotto, last of which is perhaps the best, and has various graceful narrow sections bordered by polished, twisted, grayish-blue rocks. These tend to end at deep, enclosed passages beneath dryfalls, above which the canyon is temporarily more open, so exploration requires backtracking a way then climbing up the cliffs to bypass the obstruction.

The track follows the wash into the gorge, which is at first quite wide, filled with pebbles and shifting gravel. Cliffs gradually rise at either side - made of faded, brown, crumbling rock that supports no plant life, the heat increases as any breeze in the main valley is extinguished, and the general atmosphere becomes quite oppressive. After a few wide bends the canyon constricts quite suddenly, shortly below the first 'grotto' - a cool, sheltered narrow section at the base of a 3-step dryfall, each component being around 10 feet high. 4WD vehicles can drive to within 50 yards of this point, which is said to be a good place for a picnic.

Those with suitable climbing skills may continue directly upstream but an easier option is probably to scramble up a boulder-filled ravine a little way back on the southwest side and then, after climbing quite far, follow a route on the left up to the top of the exposed ridge that separates the ravine from the main canyon, which can then be re-entered by walking back along the ridge and down the slope on the far side where this becomes less steep - joining the wash at a point just above the grotto. The ridge has nice views down to the Stovepipe Wells dunes and up to the continuation of the canyon; not far ahead this seems to disappear into a swirl of tall, colorful rocks.

Back on the streambed, the walk is through an open area for 10 minutes or so and into a second, much longer section of narrows characterized by a clean, flat sandy floor edged by weathered light grey rocks. The cliffs above overhang in a few places creating almost tunnel-like conditions, then further on they rise quite sharply, preceding an impassable dryfall of about 10 yards. This can be overcome by back-tracking again and climbing around on the left side, returning via an easy return route shortly beyond the falls. Another temporary wide part is soon replaced by more lengthy narrows, very beautiful throughout - extensive smooth, bluish-grey, sometimes marble-like channels, worn shiny in places, with occasional small dryfalls, many twists and curves. Eventually the way ahead is blocked by a 12 foot dryfall - maybe free climbable, and certainly negotiable coming back down, but if not then it may be passed by walking back once more about 100 yards and ascending a steep slope on the left, past some large barrel cacti which grow profusely at this elevation, then higher still across the rocky hillside to traverse above some sheer cliffs and finally back down to the wash.

The next narrows start quite soon and are also extensive and pretty, not quite as deep as the previous stretch but with more dryfalls and boulders in the range 3-8 feet, sometimes a little difficult to climb over. I eventually stopped at the base of a smooth 8 foot high pour-off after a walk of about 3 miles from the parking area, and a 1,500 foot elevation gain.

Overall this is an excellent canyon - just testing enough to be interesting, it has a variety of unusual narrow sections, begins after only a short walk from the trailhead and offers the likelihood of complete solitude once past the first grotto.

The track follows the wash into the gorge, which is at first quite wide, filled with pebbles and shifting gravel. Cliffs gradually rise at either side - made of faded, brown, crumbling rock that supports no plant life, the heat increases as any breeze in the main valley is extinguished, and the general atmosphere becomes quite oppressive. After a few wide bends the canyon constricts quite suddenly, shortly below the first 'grotto' - a cool, sheltered narrow section at the base of a 3-step dryfall, each component being around 10 feet high. 4WD vehicles can drive to within 50 yards of this point, which is said to be a good place for a picnic.

Those with suitable climbing skills may continue directly upstream but an easier option is probably to scramble up a boulder-filled ravine a little way back on the southwest side and then, after climbing quite far, follow a route on the left up to the top of the exposed ridge that separates the ravine from the main canyon, which can then be re-entered by walking back along the ridge and down the slope on the far side where this becomes less steep - joining the wash at a point just above the grotto. The ridge has nice views down to the Stovepipe Wells dunes and up to the continuation of the canyon; not far ahead this seems to disappear into a swirl of tall, colorful rocks.

Back on the streambed, the walk is through an open area for 10 minutes or so and into a second, much longer section of narrows characterized by a clean, flat sandy floor edged by weathered light grey rocks. The cliffs above overhang in a few places creating almost tunnel-like conditions, then further on they rise quite sharply, preceding an impassable dryfall of about 10 yards. This can be overcome by back-tracking again and climbing around on the left side, returning via an easy return route shortly beyond the falls. Another temporary wide part is soon replaced by more lengthy narrows, very beautiful throughout - extensive smooth, bluish-grey, sometimes marble-like channels, worn shiny in places, with occasional small dryfalls, many twists and curves. Eventually the way ahead is blocked by a 12 foot dryfall - maybe free climbable, and certainly negotiable coming back down, but if not then it may be passed by walking back once more about 100 yards and ascending a steep slope on the left, past some large barrel cacti which grow profusely at this elevation, then higher still across the rocky hillside to traverse above some sheer cliffs and finally back down to the wash.

The next narrows start quite soon and are also extensive and pretty, not quite as deep as the previous stretch but with more dryfalls and boulders in the range 3-8 feet, sometimes a little difficult to climb over. I eventually stopped at the base of a smooth 8 foot high pour-off after a walk of about 3 miles from the parking area, and a 1,500 foot elevation gain.

Overall this is an excellent canyon - just testing enough to be interesting, it has a variety of unusual narrow sections, begins after only a short walk from the trailhead and offers the likelihood of complete solitude once past the first grotto.

Telescope Peak Hike (Only for those in great physical condition!)

Length: 14 miles, round trip.

Starting Point: Mahogany Flat Campground, upper Wildrose Canyon Road. Rough, steep road after Charcoal Kilns.

Description: Strenuous trail to highest peak in the park (11,049 ft.) with a 3,000 ft. elevation gain. Ancient bristlecone pines appear just above the 10,000 ft. level. The summit rewards you with spectacular views ranging from Badwater, the lowest point in the Western Hemisphere to the east, to Mt. Whitney, the highest point in the lower 48 United States to the west. Climbing this peak in the winter requires ice axe and crampons, and is only advised for experienced climbers. Telescope Peak is usually snow-free by June. Don't forget that the high altitude may slow you down.

From Panamnit Springs take California Highway 190 east about 21 miles and take Emigrant Canyon Road south up and over Emigrant Pass about 21 miles and turn left up Wildrose Canyon. Pass the Wildrose Charcoal Kilns at about 7 miles up this road. The last 3 miles of the road are unpaved and the road is subject to storm closures. Continue past the kilns another two miles to Mahogany Flat Campground where you’ll find the trailhead.

Starting Point: Mahogany Flat Campground, upper Wildrose Canyon Road. Rough, steep road after Charcoal Kilns.

Description: Strenuous trail to highest peak in the park (11,049 ft.) with a 3,000 ft. elevation gain. Ancient bristlecone pines appear just above the 10,000 ft. level. The summit rewards you with spectacular views ranging from Badwater, the lowest point in the Western Hemisphere to the east, to Mt. Whitney, the highest point in the lower 48 United States to the west. Climbing this peak in the winter requires ice axe and crampons, and is only advised for experienced climbers. Telescope Peak is usually snow-free by June. Don't forget that the high altitude may slow you down.

From Panamnit Springs take California Highway 190 east about 21 miles and take Emigrant Canyon Road south up and over Emigrant Pass about 21 miles and turn left up Wildrose Canyon. Pass the Wildrose Charcoal Kilns at about 7 miles up this road. The last 3 miles of the road are unpaved and the road is subject to storm closures. Continue past the kilns another two miles to Mahogany Flat Campground where you’ll find the trailhead.

Marble Canyon Hike

The road to Cottonwood and Marble Canyons begins just east of the Stovepipe Wells airstrip. This is 30 miles east on 190 from Panamint Springs. The road travels up the broad alluvial fan before reaching the canyon mouth. About 8.0 miles in, the road drops into the wash and becomes rocky and rough. About 1.0 mile past the end of the first narrows, a side road leads up Marble Canyon. At road's end, continue on foot to see some of the finest canyon narrows in the park. There are petroglyphs in the second narrows.

Natural Bridge Hike

A path leads a quarter mile from the parking area into the canyon. Water rushing through cracks in the weaker strata gradually undercut the rock and left a large natural bridge formation. It now looms 50 feet above the wash. Beyond, part of the canyon wall has been eroded into a grotto.

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel south on 190 about 1.6 miles and turn right onto Badwater Road. Drive south on Badwater Road about 13 miles and turn left and go about 1.7 miles on the dirt road which leads to the Natural Bridge trailhead.

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel south on 190 about 1.6 miles and turn right onto Badwater Road. Drive south on Badwater Road about 13 miles and turn left and go about 1.7 miles on the dirt road which leads to the Natural Bridge trailhead.

Dante's View

Nearly a mile above Badwater is Dante’s View. From this viewpoint you can nearly see all of Death Valley including the lowest point at Badwater to the highest at Telescope Peak a difference of 11,329 feet. Not much here except the fantastic view, deserving of a "WOW" when first seen.

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel south on 190 about 10.7 miles and turn right onto Furnace Creek Road. Travel about 7.4 miles and bear right onto Dante’s View Road. Another 5.5 miles brings you to the Dante’s View lookout.

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel south on 190 about 10.7 miles and turn right onto Furnace Creek Road. Travel about 7.4 miles and bear right onto Dante’s View Road. Another 5.5 miles brings you to the Dante’s View lookout.

Harmony Borax Works

From the Harmony Borax Works, Death Valley's mule teams hauled borax to the railroad town of Mojave, 165 mi away. The teams plied the route until 1889, when the railroad finally arrived in Zabriskie. Constructed in 1883, one of the oldest buildings in Death Valley houses the Borax Museum. Originally a miners' bunkhouse, the building once stood in Twenty Mule Team Canyon. Now it displays mining machinery and historical exhibits. The adjacent structure is the original mule-team barn.

In the Furnace Creek area, borates were deposited in the remains of old lakebeds. Later, partial alteration and solution of these veins by groundwater moved some of the borates to the Death Valley floor where evaporation has left a mixed crust of salt, borates, and alkalies. Aaron Winters found borax on the Death Valley saltpan in 1881. He soon sold his claims to William T. Coleman, builder of the Harmony Borax Works, where borate-bearing muds were refined until 1889.

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel north on 190 about one mile and turn left to find the Harmony Borax Works.

In the Furnace Creek area, borates were deposited in the remains of old lakebeds. Later, partial alteration and solution of these veins by groundwater moved some of the borates to the Death Valley floor where evaporation has left a mixed crust of salt, borates, and alkalies. Aaron Winters found borax on the Death Valley saltpan in 1881. He soon sold his claims to William T. Coleman, builder of the Harmony Borax Works, where borate-bearing muds were refined until 1889.

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel north on 190 about one mile and turn left to find the Harmony Borax Works.

Zabriskie Point

As well as being the title of a curious film by Antonioni (1969), Zabriskie Point is an elevated overlook of a colorful, undulating landscape of gullies and mud hills at the edge of the Funeral Mountains, a few miles from Death Valley - from the viewpoint, the flat salt plains on the valley floor are visible in the distance. In the past it was possible to drive right to the edge of the overlook, and several minutes of the film was set there, but since then a new larger car-park has been constructed lower down and visitors now have a short walk uphill. Most people do little more than briefly admire the scenery, which is best at sunrise, but it is possible to climb some of the adjacent hills to get a better overall view, or wander down amongst the variegated dunes. A foot-path leads through the mounds, down a ravine and into Gower Gulch after 2 miles, while another branch veers right into Golden Canyon.

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel south on 190 about 3.5 miles and turn right onto short road to the Zabriskie Point lookout.

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel south on 190 about 3.5 miles and turn right onto short road to the Zabriskie Point lookout.

Furnace Creek Golf Course

The 18-hole Furnace Creek Golf Course, the world’s lowest golf course at 214 feet below sea level, is an oasis championship course. Originally opened in 1931, the course underwent a major renovation in 1997 by world-renowned golf course architect Perry Dye. Due to the elevation of the course, a slightly greater gravity and barometric pressure force are present. Frequent golfers have noticed a distinct difference in how the ball responds in relation to other courses at or above sea level. Green fees are $55.00 (2005).

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel south on 190 one-quarter mile. The golf course is on the right.

From the Furnace Creek Campground, travel south on 190 one-quarter mile. The golf course is on the right.

Skidoo Ghost Town

In January 1906 two wandering prospectors, John Ramsey and John (One-Eye) Thompson were headed towards the new gold strike at Harrisburg. Along the way a blinding fog came in and the two camped near Emigrant Spring for fear of getting lost. When the fog lifted they noticed some ledges with promising colors. They filed their claims and kept news of their strike quiet for a couple of months. Bob Montgomery purchased their group of claims entitled the Gold Eagle group. Plans were made that by Jan. 1907. a quartz mill would be installed. Water came from Emigrant Spring, five miles away by trail and seven by wagon. This couldn’t provide enough water for the operation though, so plans were made to acquire the water rights of some springs near Telescope Peak. The water was to flow by gravity pressure from Birch Spring to the mill in a long pipeline ranging from 6-10 inches in diameter. It was estimated to cost $150,000 and fall 1800 feet to generate enough force for mining and milling. It was to be strung in 20-ft. lengths, weighing 650 pounds a length with 18 miles weighing 1544 2/5 tons.

By July 4, 1906, the town seemed assured of success. Plans had already been made for an auto line from Beatty, a stage line seemed definite, application had been made for a post office and with its high altitude (5600 ft.) production could continue all summer. By the end of August 1906 a townsite had been marked out. No one will ever know exactly how the town got its name, 23 Skidoo. Possibilities include the 23 mile water line (which is actually 22 miles long), the 23 claims initially flied, the location of the claim on the 23rd of January, and the 23 men who founded the town.

By March of 1907, Skidoo boasted 400-500 citizens and had stores offering mining equipment, hardware, clothing, dry goods and groceries. There were saloons, a newspaper, restaurants, a physician, and lawyers. By April the town had 130 homes and businesses of frame, wood and iron. A phone line had been completed to Rhyolite, permitting outside communication. In November 1907, the pipeline was finally completed and water flowed into Skidoo. Final tally on the cost was $250,000. The financial panic of 1907 affected the town by reducing plans for additional businesses. By the fall of 1908 mining activity had slowed tremendously in Skidoo due to the scarcity of mills in the area.

Mining activity ebbed and flowed over the next several years and in September 1917, the rich vein was played out and the mine closed down for the last time. By 1922 several buildings were still standing along one street and an old prospector "Old Tom Adams" was the lone citizen. In 1923 Skidoo was one of the location sites for the Hollywood film, "Greed" which was the first feature film made in the Death Valley area.

Skidoo was one of the last gold mining camps in Death Valley. One of the unique features of the mining operation in Skidoo was the mining of large amounts of gold ore by going into narrow ore veins using large-scale mining efforts. The pipeline to Skidoo is considered to be a marvelous feat of engineering. It crossed from Skidoo over Harrisburg Flats and Wood, Nemo, and Wildrose Canyons to the Telescope Peak area.

From Panamnit Springs take California Highway 190 east about 21 miles and take Emigrant Canyon Road south a bit over 9 miles to Skidoo Road. Turn left on the dirt Skidoo Road and travel another 7.5 miles to Skidoo.

By July 4, 1906, the town seemed assured of success. Plans had already been made for an auto line from Beatty, a stage line seemed definite, application had been made for a post office and with its high altitude (5600 ft.) production could continue all summer. By the end of August 1906 a townsite had been marked out. No one will ever know exactly how the town got its name, 23 Skidoo. Possibilities include the 23 mile water line (which is actually 22 miles long), the 23 claims initially flied, the location of the claim on the 23rd of January, and the 23 men who founded the town.

By March of 1907, Skidoo boasted 400-500 citizens and had stores offering mining equipment, hardware, clothing, dry goods and groceries. There were saloons, a newspaper, restaurants, a physician, and lawyers. By April the town had 130 homes and businesses of frame, wood and iron. A phone line had been completed to Rhyolite, permitting outside communication. In November 1907, the pipeline was finally completed and water flowed into Skidoo. Final tally on the cost was $250,000. The financial panic of 1907 affected the town by reducing plans for additional businesses. By the fall of 1908 mining activity had slowed tremendously in Skidoo due to the scarcity of mills in the area.

Mining activity ebbed and flowed over the next several years and in September 1917, the rich vein was played out and the mine closed down for the last time. By 1922 several buildings were still standing along one street and an old prospector "Old Tom Adams" was the lone citizen. In 1923 Skidoo was one of the location sites for the Hollywood film, "Greed" which was the first feature film made in the Death Valley area.

Skidoo was one of the last gold mining camps in Death Valley. One of the unique features of the mining operation in Skidoo was the mining of large amounts of gold ore by going into narrow ore veins using large-scale mining efforts. The pipeline to Skidoo is considered to be a marvelous feat of engineering. It crossed from Skidoo over Harrisburg Flats and Wood, Nemo, and Wildrose Canyons to the Telescope Peak area.

From Panamnit Springs take California Highway 190 east about 21 miles and take Emigrant Canyon Road south a bit over 9 miles to Skidoo Road. Turn left on the dirt Skidoo Road and travel another 7.5 miles to Skidoo.

Cerro Gordo Mine & Ghost Town

4WD-ish Route to historic mine and ghost town

Situated near the summit of Buena Vista Peak at an elevation of 8,500 feet, the isolated mining outpost became known as Cerro Gordo, meaning "fat hill", the meaning, of course, that it was fat with silver. The principal mines at this time were the San Lucas, San Ygnacio, San Francisco, and San Felipe. Within four years, the number of mining claims would increase to more than seven hundred.

The Mexicans processed their ore in crude adobe and stone ovens called "vasos". These primitive furnaces directed the heat from the open-hearth across the ore and reflected it downward from the low roof, rather than heating from directly below. The ore was thus "roasted" until the silver was extracted.

Cerro Gordo's ore was of such high quality, that, even the Mexican vasos extracted a larger amount of silver than might have been expected. Although their success attracted a few Americans, little effort was directed toward underground development of the deposits. The miners on this mountain had no capital except their own labor with which to develop the mines. Other obstacles also restricted Cerro Gordo's growth, these being mainly the ruggedness of terrain, scarcity of water on the mountain top, and the location remote from any settlement with a large population.

Unlike most boom towns of its day, Cerro Gordo did not come into being overnight. To the contrary, the mining camp high in the Inyo's seemed almost reluctant to become California's greatest silver producer. The first real effort to develop any of the claims was made on the San Lucas mine in 1866 by Jose Ochoa, who was extracting about 1112 tons of ore every 12 hours. The silver ore was transported in sacks by pack animals to the Silver Sprout Mill a few miles west of Fort Independence. It was probably these shipments of silver ore, yielding $300 a ton, that first attracted the attention of Victor Beau dry, a successful merchant at Fort Independence.

Cerro Gordo Road is a maintained gravel/dirt road, just short of 8 miles long and fairly steep in places. You gain a mile in elevation from bottom to top. 4WD is not required, but recommended.

Situated near the summit of Buena Vista Peak at an elevation of 8,500 feet, the isolated mining outpost became known as Cerro Gordo, meaning "fat hill", the meaning, of course, that it was fat with silver. The principal mines at this time were the San Lucas, San Ygnacio, San Francisco, and San Felipe. Within four years, the number of mining claims would increase to more than seven hundred.

The Mexicans processed their ore in crude adobe and stone ovens called "vasos". These primitive furnaces directed the heat from the open-hearth across the ore and reflected it downward from the low roof, rather than heating from directly below. The ore was thus "roasted" until the silver was extracted.

Cerro Gordo's ore was of such high quality, that, even the Mexican vasos extracted a larger amount of silver than might have been expected. Although their success attracted a few Americans, little effort was directed toward underground development of the deposits. The miners on this mountain had no capital except their own labor with which to develop the mines. Other obstacles also restricted Cerro Gordo's growth, these being mainly the ruggedness of terrain, scarcity of water on the mountain top, and the location remote from any settlement with a large population.

Unlike most boom towns of its day, Cerro Gordo did not come into being overnight. To the contrary, the mining camp high in the Inyo's seemed almost reluctant to become California's greatest silver producer. The first real effort to develop any of the claims was made on the San Lucas mine in 1866 by Jose Ochoa, who was extracting about 1112 tons of ore every 12 hours. The silver ore was transported in sacks by pack animals to the Silver Sprout Mill a few miles west of Fort Independence. It was probably these shipments of silver ore, yielding $300 a ton, that first attracted the attention of Victor Beau dry, a successful merchant at Fort Independence.

Cerro Gordo Road is a maintained gravel/dirt road, just short of 8 miles long and fairly steep in places. You gain a mile in elevation from bottom to top. 4WD is not required, but recommended.

More Death Valley Places we're not going...

- Saline Valley Dunes

- Saline Valley Hot Springs

- Darwin Townsite

- Ballarat Ghost Town

- Trona Pinnacles

- Wildrose Peak Hike

- Cottonwood Canyon

- Harmony Borax Works Interpretive Trail

- Eureka Mine

- Aguereberry Point

- Borax Museum

- Gower Gulch

- Scotty’s Castle

- Greenwater Valley

- Devil’s Hole

- Death Valley Dunes

- Panamint Dunes

- Eagle Borax Works

- Ashford Mill Site

- Shore Line Butte

- Echo Canyon

- Keane Wonder Mine

- Ubehebe Crater

- Saratoga Springs

- Mengel Pass

- Barker Ranch

- Saline Valley Hot Springs

- Darwin Townsite

- Ballarat Ghost Town

- Trona Pinnacles

- Wildrose Peak Hike

- Cottonwood Canyon

- Harmony Borax Works Interpretive Trail

- Eureka Mine

- Aguereberry Point

- Borax Museum

- Gower Gulch

- Scotty’s Castle

- Greenwater Valley

- Devil’s Hole

- Death Valley Dunes

- Panamint Dunes

- Eagle Borax Works

- Ashford Mill Site

- Shore Line Butte

- Echo Canyon

- Keane Wonder Mine

- Ubehebe Crater

- Saratoga Springs

- Mengel Pass

- Barker Ranch